Provided by Michael J. Loochtan, MD

Ear infections are one of the most common disorders to that affect children. These can often be managed with medication without the need for further intervention. Sometimes, however, your child’s doctor may recommend that your child have an evaluation with an otolaryngologist. Below is an explanation of what ENTs are, a discussion of normal ear anatomy, and an explanation of when ear infections may warrant consideration for ear tube placement.

WHAT IS AN OTOLARYNGOLOGIST (ENT)?

An ENT is a doctor who is specially trained to diagnose and treat disorders of the ears, nose, and throat medically or surgically if needed. Therefore, they are also called head & neck surgeons. It’s a mouthful to say “Otolaryngologist – Head & Neck Surgeon” therefore usually we just go by “ENT.” ENT training is quite rigorous and entails 4 years of medical school after college, followed by 5 years of residency training. Some ENTs pursue additional specialized training after residency. This extra training is called a fellowship and is usually 1-2 years in length.

WHAT ARE THE PARTS OF THE EAR?

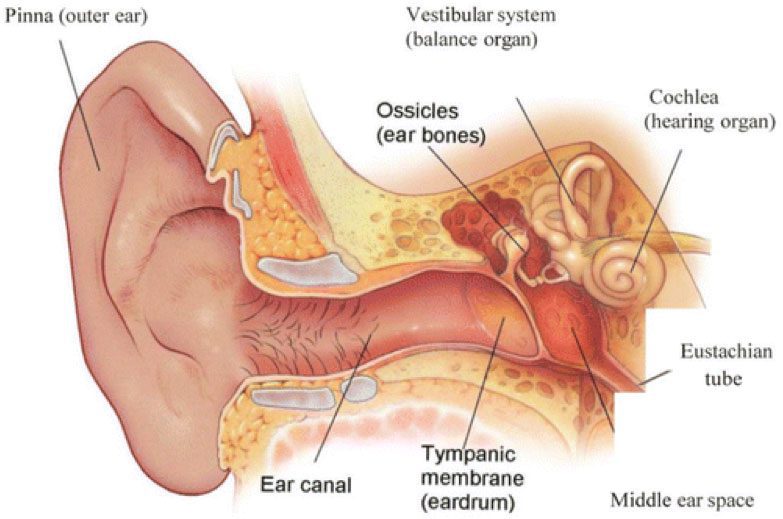

Please see the diagram below.

Rosenfeld RM. A Parent’s Guide to Ear Tubes. Hamilton, Ontario, Canada: BC Decker; 2005. Reproduced with permission.

Outer Ear

When many people think of ears, they think of the part they can see. This is called the auricle or pinna. This is the part of the ear that we can see with our naked eyes without any special instruments. This part of the ear is made up of skin that tightly surrounds a cartilage scaffolding. The bottom part of your auricle is called the lobe (or lobule), and is made up of skin and fatty tissue. This is the part of the ear that is most commonly pierced by earrings. In the center of your outer ear is a small hole called the external auditory canal (ear canal) which is a small tunnel that leads to the ear drum (tympanic membrane). Even though you cannot see most of the ear canal, this is also part of the outer ear. The ear canal is lined by skin, beneath which the outer portion is cartilage and the deeper portion is bone. This portion of the ear is where earwax (cerumen) is made.

Middle Ear

The ear canal leads to the ear drum (tympanic membrane). The ear drum protects the middle and inner ear structures from the outside world. The ear drum is also connected to one of the ear bones called the malleus. The ear drum amplifies sound that is directed from the outer ear and transmits this sound to the ear bones (ossicles) which then transmit sound to the inner ear. Connected to the middle ear is a special tunnel called the Eustachian tube. This tube is primarily composed of cartilage and is connected to the muscles in the back of the throat. This tube opens into the back of the nose at the junction of the nose and throat in a region called the nasopharynx. The Eustachian tube opens and closes many times per day to allow air into and out of the middle ear space (behind the ear drum). This is the same tube that opens and closes when you ride on an airplane and feel you ears “pop.” In many children and some adults, sometimes these tubes do not function properly, and can result in Eustachian tube dysfunction (ETD). This results in the accumulation of fluid in the middle ear and is known as otitis media. This fluid can cause hearing loss, balance problems, ear discomfort, or other symptoms.

Inner Ear

The inner ear is composed of a snail shaped bone called the cochlea as well as bony balance canals (semicircular canals). The third ear bone (stapes or stirrup) fits into the inner ear like a piston its vibration moves fluid in the inner ear which then creates an electrical signal that travels to the brain via the cochlear nerve (hearing nerve). Your brain then interprets this signal as sound.

Below is some very helpful information from the American Academy Of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) regarding ear tubes (reproduced with permission). More information can be found at https://www.entnet.org//content/ear-tubes

Painful ear infections are a rite of passage for children and by the age of five, nearly every child has experienced at least one episode. Most ear infections either resolve on their own (viral) or are effectively treated by antibiotics (bacterial). But sometimes ear infections and/or fluid in the middle ear may become a chronic problem leading to other issues, such as hearing loss, poor school performance, or behavior and speech problems. In these cases, insertion of an ear tube by an otolaryngologist (ear, nose, and throat specialist) may be considered.

According to the American Academy of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery, “consultation with an otolaryngologist may be warranted if you or your child has experienced repeated or severe ear infections, ear infections that are not resolved with antibiotics, hearing loss due to fluid in the middle ear, barotrauma, or have an anatomic abnormality that inhibits drainage of the middle ear.”

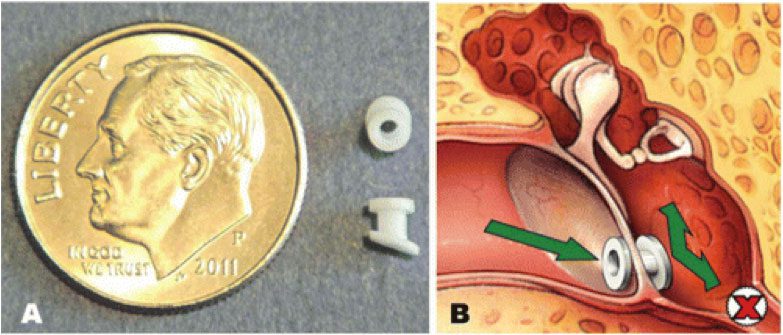

WHAT ARE EAR TUBES?

Ear tubes are tiny cylinders placed through the ear drum (tympanic membrane) to allow air into the middle ear. They also may be called tympanostomy tubes, myringotomy tubes, ventilation tubes, or PE (pressure equalization) tubes.

These tubes can be made out of various materials and come in two basic types: short-term and long-term. Short- term tubes are smaller and typically stay in place for six to eighteen months before falling out on their own. Long-term tubes are larger and have flanges that secure them in place for a longer period of time. Long-term tubes may fall out on their own, but removal by an otolaryngologist may be necessary.

Rosenfeld RM. A Parent’s Guide to Ear Tubes. Hamilton, Ontario, Canada: BC Decker; 2005. Reproduced with permission.

WHO NEEDS EAR TUBES AND WHY?

Ear tubes may be recommended when a person experiences repeated middle ear infection (acute otitis media) or has hearing loss caused by persistent middle ear fluid (otitis media with effusion). These conditions most commonly occur in children, but can also be present in teens and adults and can lead to speech and balance problems, hearing loss, poor school performance, or changes in the structure of the ear drum. Other less common conditions that may warrant the placement of ear tubes are malformation of the ear drum or eustachian tube, Down Syndrome, cleft palate, and barotrauma (injury to the middle ear caused by a reduction of air pressure, usually seen with altitude changes as in flying and scuba diving).

Each year, more than half a million ear tube surgeries are performed on children, making it the most common childhood surgery performed with anesthesia. The average age for ear tube insertion is one to three years old. Inserting ear tubes may:

- Reduce the risk of future ear infection;

- Restore hearing loss caused by middle ear fluid;

- Improve speech problems and balance problems; and

- Improve behavior and sleep problems caused by chronic ear infections; and

- Help children do their best in school.

HOW ARE EAR TUBES INSERTED IN THE EAR?

Ear tubes are inserted through an outpatient surgical procedure called a myringotomy. A myringotomy refers to an incision (small opening) in the ear drum or tympanic membrane, which is most often done under a surgical microscope with a small scalpel. If an ear tube is not inserted, the hole would heal and close within a few days. To prevent this, an ear tube is placed in the hole to keep it open and allow air to reach the middle ear space (ventilation).

WHAT HAPPENS DURING SURGERY?

Most young children require general anesthesia but some doctors can do this as a brief office procedure. Some older children and adults may also be able to tolerate the procedure without anesthetic. A myringotomy is performed and the fluid behind the ear drum (in the middle ear space) is suctioned out. The ear tube is then placed in the opening. Ear drops may be administered after the ear tube is placed and may be prescribed for a few days. The procedure usually lasts less than 15 minutes and patients recover very quickly.

Sometimes the otolaryngologist will recommend removal of the adenoid tissue (lymph tissue located in the upper airway behind the nose) when ear tubes are placed for persistent middle-ear fluid. This is effective for children four years or older and is often considered when a repeat tube insertion is necessary. Current research indicates that removing adenoid tissue concurrent with placement of ear tubes for persistent middle-ear fluid can reduce the risk of recurrent ear infections and the need for repeat surgery in children four years and older.

WHAT HAPPENS AFTER SURGERY?

After surgery, the patient is monitored in the recovery room (if general anesthesia was used) and will usually go home within an hour or two if no complications occur. Patients usually experience little or no postoperative pain, but grogginess, irritability, and/or nausea from the anesthesia can occur temporarily. When done in the office recovery is immediate.

Hearing loss caused by the presence of middle ear fluid is immediately resolved by surgery. Children with speech, language, learning, or balance problems may take several weeks or months to fully improve.

The otolaryngologist will provide specific postoperative instructions, including when to seek attention and to set follow-up appointments. He or she may also prescribe an antibiotic ear drops for a few days. An audiogram should be performed after surgery, if hearing loss is present before the tubes are placed. This test will make sure that hearing has improved with the surgery.

Although the tube does have a small opening (about 1/20th of an inch) that could allow water to enter the middle ear, research studies show no benefit in keeping the ears dry and current guidelines do not recommend routine water precautions. Therefore, you do not need to restrict swimming or bathing while tubes or in place and do not need to use earplugs, head bands, or other water-tight devices unless specifically recommended by your doctor.

POSSIBLE COMPLICATIONS

Myringotomy with insertion of ear tubes is an extremely common and safe procedure with minimal complications. When complications do occur, they may include:

- Perforation: This can rarely happen when a tube comes out or a long-term tube is removed and the hole in the tympanic membrane (ear drum) does not close. The hole can be patched through a surgical procedure called a tympanoplasty or myringoplasty.

- Scarring: Any irritation of the ear drum (recurrent ear infections), including repeated insertion of ear tubes, can cause scarring called tympanosclerosis or myringosclerosis. In most cases, this causes no problem with hearing and does not need any treatment.

- Infection: Ear infections can still occur with a tube in place and cause ear discharge or drainage. However, these infections are usually infrequent, do not cause hearing loss (because the infection drains out), and may go away on their own or be treated effectively with antibiotic ear drops. Oral antibiotics are rarely needed.

- Ear tubes come out too early or stay in too long: If an ear tube expels from the ear drum too soon (which is unpredictable), fluid may return and repeat surgery may be needed. Ear tubes that remain too long may result in perforation or may require removal by an otolaryngologist.